Financial Times, September 25 2017

https://www.ft.com/content/f19f4944-a11a-11e7-b797-b61809486fe2

Jonathan Ford

When prices tumble for a product or service, there is generally an observable reason. It might be a cunning technological fix that dramatically boosts productivity, for instance, or the sudden slide in a key input cost. But nothing so obvious can convincingly explain why it is suddenly much cheaper to produce electricity from offshore wind turbines.

***

Check also:

Subsidy-Free Wind Farms Risk Ruining the Industry’s Reputation. By Jess Shankleman

Bloomberg,

http://www.bipartisanalliance.com/2017/09/subsidy-free-wind-farms-risk-ruining.html

***

The latest round of renewable auctions has seen two big projects awarded contracts guaranteeing a fixed price of £57.50 per megawatt hour for their output when the blades start turning sometime in the next decade. That is a very big dip from the first round, which required subsidies of some £150/MWh to be profitable. Even the cheapest of previous vintages were north of £110.

It is not so long since British wind power bosses were vowing — amid widespread scepticism — that they could reduce costs to £100/MWh by 2020. Yet these auction results suggest a far steeper decline in offshore costs.

Of course, it is always worth peering behind the headlines to put numbers in context. The sums quoted are 2012 prices. The actual figure in today’s money is therefore £64/MWh; a still subsidy-rich 50 per cent above the current wholesale price of about £40.

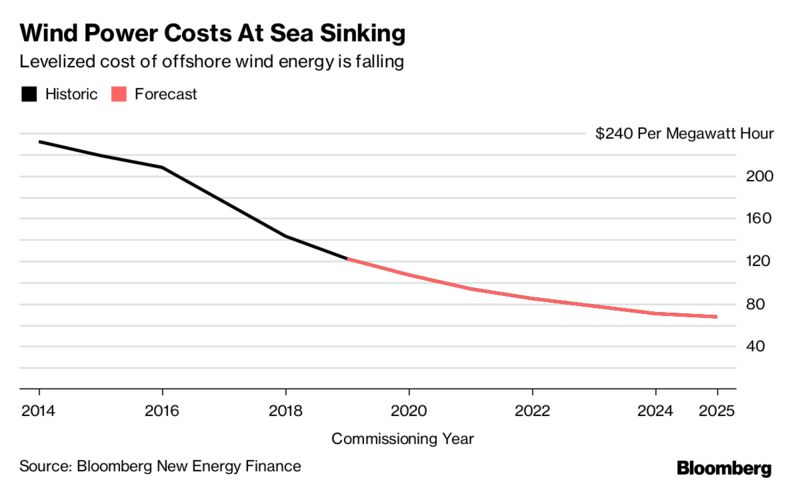

The real question though is how the industry can support such a reduction. Take overall costs, for instance. Most studies do not yet point to projects breaking even at £57.50. According to a recent review by the UK’s Offshore Wind Programme Board, so-called levelised costs for new wind projects at the point of commitment (ie not yet built, but button decisively pressed) declined by 7 per cent annually from £142/MWh in 2010-11 to just £97 in 2015-16, driven by factors such as the use of larger turbines and better siting. But while these are impressive figures even they cannot explain a further £40 drop in such a short space of time.

What’s more, by far the biggest component of those costs is capital expenditure, and another study suggests that progress here is much more nuanced. A new report led by Gordon Hughes, a former professor of economics at Edinburgh University, and published by the sceptical Global Warming Policy Foundation, has analysed the reported capital costs of 86 projects across Europe. These show that while technological advances are driving down costs by 4 per cent annually, this gain is being offset as the industry moves out into deeper and more challenging waters. So, depending on where future projects are sited, there may even be no clear downward trend at all.

It may be possible that the auction-winning projects have specific reasons for being able to deliver low prices. For instance, the Hornsea II project sponsored by Denmark’s Dong Energy sits next to a first farm that is also being built by the same company (at far higher rates of subsidy), offering the opportunity to share support infrastructure, as well as the link between the turbines and the grid.

But it is also possible that the promoters view the CFD contract as a pretty loose commitment. “Potentially these bids could be seen as more of an option on future capacity,” said Allan Baker, Société Générale’s global head of power advisory and project finance at Bloomberg’s New Energy Finance Summit last week.

Just three giant wind farms have taken all the capacity in the current auction, which at 3.2GW is equivalent to 60 per cent of Britain’s current offshore fleet. That means the competition is in effect shut out.

The contracts do not represent an absolute commitment. According to the UK government, the developers could withdraw were they unable to obtain financing, with only a limited penalty. What they would mainly lose was the right to pop the same project into a later auction round.

So to the extent, for instance, that contracts depend on yet-to-be developed technologies, such as 15MW turbines, or squeezing contractor prices, there would be little cost to cancelling were developers not to get the deals they hoped for.

And even beyond construction, the CFD could conceivably be revoked by the operator were it prepared to pay a significant, not ruinous, financial penalty, Prof Hughes reckons. So should wholesale prices rise well above the level of the fixed strike price in future, developers might be able to flip across and benefit from (superior) market rates. That might happen, for instance, were the government to introduce a higher carbon price.