Quantifying Structural Subsidy Values for Systemically Important Financial Institutions. By Kenichi Ueda and Beatrice Weder

IMF Working Paper No. 12/128

Summary: Claimants to SIFIs receive transfers when governments are forced into bailouts. Ex ante, the bailout expectation lowers daily funding costs. This funding cost differential reflects both the structural level of the government support and the time-varying market valuation for such a support. With large worldwide sample of banks, we estimate the structural subsidy values by exploiting expectations of state support embedded in credit ratings and by using long-run average value of rating bonus. It was already sizable, 60 basis points, as of the end-2007, before the crisis. It increased to 80 basis points by the end-2009.

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25928.0

Excerpts

Introduction

One of the most troubling legacies of the financial crisis is the problem of “too-systemically important-to-fail” financial institutions. Public policy had long recognized the dangers that systemically relevant institutions pose for the financial system and for public sector balance sheets, but in practice, this problem was not deemed to be extremely pressing. It was mainly dealt with by creating some uncertainty (constructive ambiguity) about the willingness of government intervention in a crisis.

The recent crisis since 2008 provided a real-life test of the willingness to intervene. After governments have proven their willingness to extended large-scale support, constructive ambiguity has given way to near certainty that sufficiently large or complex institutions will not be allowed to fail. Thus, countries have emerged from the financial crisis with an even larger problem: Many banks are larger than before and so are implicit government guarantees. In addition, it also becomes clear that these guarantees are not limited to large institutions. In Europe, smaller institutions with a high degree of interconnectedness, complexity, or political importance were also considered too important to fail.

The international community is addressing the problem of SIFIs with a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, the probability of SIFIs failure is to be reduced through higher capital buffers and tighter supervision. On the other hand, SIFIs are to be made more “resolvable” by subjecting them to special resolutions regimes (e.g., living wills and CoCos). A number of countries have already adopted special regimes at the national level or are in the process of doing so. However, it remains highly doubtful whether these regimes would be operable across borders. This regulatory coordination failure implies that creditors of SIFIs continue to enjoy implicit guarantees.

Subsidies arising from size and complexity create incentives for banks to become even larger and more complex. Hence, eliminating the value of the implicit structural subsidy to SIFIs should contribute to reducing both the probability and magnitude of (future) financial crises. Market participants tend to dismiss these concerns by stating that these effects may be there in theory but are very small in practice. Therefore, it requires an empirical study to quantify the value of state subsidies to SIFIs. This is the aim of this paper.

How can we estimate the value of structural state guarantees? As institutions with state backing are safer, investors ask for a lower risk premium, taking into account the expected future transfers from the government. Therefore, before crisis, the expected value of state guarantees is the difference in funding costs between a privileged bank and a non-privileged bank. A caveat of this reasoning is that this distortion might affect the competitive behaviors and the market shares of both the subsidized and the non-subsidized financial institutions. Therefore, the difference in observed funding costs may include indirect effects in addition to the direct subsidy for SIFIs.

We estimate the value of the structural subsidy using expectations of government support embedded in credit ratings. Overall ratings (and funding costs) of financial institutions have two constituent parts: their own financial strength and the expected amount of external support. External support can be provided by a parent company or by the government. Some rating agencies (e.g., Fitch) provide regular quantitative estimates of the probability that a particular financial institution would receive external support in case of crisis. We isolate the government support component and provide estimates of the value of this subsidy as of end-2007 and end-2009.

We find that the structural subsidy value is already sizable as of end-2007 and increased substantially by the end-2009, after key governments confirmed bailout expectations. On average, banks in major countries enjoyed credit rating bonuses of 1.8-3.4 at the end-2007 and 2.5-4.2 at the end-2009. This can be translated into a funding cost advantage roughly 60bp and 80bp, respectively.

The use of ratings might be considered problematic because rating agencies have been known to make mistakes in their judgments. For instance, they have been under heavy criticism for overrating structured products in the wake of the financial crisis. However, whether rating agencies assess default risks correctly is not important for the question at hand. All that matters is that markets use ratings in pricing debt instruments and those ratings influence funding costs. This has been the case.6 Therefore, we can use the difference in overall credit ratings of banks as a proxy for the difference in their structural funding costs. Our empirical approach is to extract the value of structural subsidy from support ratings, while taking into account bank-specific factors that determine banks’ own financial strength as well as country-specific factors that determine governments’ fiscal ability to offer support.

A related study by Baker and McArthur (2009) obtains a somewhat lower value of the subsidy, ranging from 9 bp to 49 bp. However, the difference in results can be explained by different empirical strategies: Baker and McArthur use the change in the difference in funding costs between small and large US banks before and after TARP. With this technique, they identify the change in the value of the SIFIs subsidy, which is assumed to be created by the government bailout intervention. However, they cannot account for a possible level of bailout expectations that may have been embedded in prices long before the financial crisis. This ignorance is a drawback of all studies that use bailout events to quantify the value of subsidy: They can be quite precise in estimating the change in the subsidy due to a particular intervention but they will underestimate the total level of the subsidy if the support is positive even in tranquil times. In other words, they cannot establish the value of funding cost advantages accruing from expected state support even before the crisis.

This characteristic is the distinct advantage of the rating approach. It allows us to estimate not only the change of the subsidy during the crisis but also the total value of the subsidy before the crisis. As far as we are aware, there are only a few previous papers which use ratings. Soussa (2000), Rime (2005), and Morgan and Stiroh (2005) used similar approaches to back out the value of the subsidy. However, our study is more comprehensive by including a larger set of banks and countries and also by covering the 2008 financial crisis.

Assuming that the equity values are not so much affected by bailouts but the debt values are, the time-varying estimates of the government guarantees can be calculated using a standard option pricing theory.9 However, the funding cost advantage in crisis reflects two components: first, the structural government support and, second, a larger risk premium due to market turmoil. If we calculate the value of one rating bonus only in crisis times, the value of bonus would be larger because of the latter effect. However, when designing a corrective levy, the value of the government support should not be affected by these short-run market movements. For this reason, the long-run average value of one rating bonus—used here to calculate the total value of the structural government support—should be more suitable as a basis for a collective levy than real-time estimates for the market value of the government guarantees.

Interpretation and conclusion

Section III has provided estimates of the value of the subsidy to SIFIs in terms of the overall ratings. Using the range of our estimates, we can summarize that a one-unit increase in government support for banks in advanced economies has an impact equivalent to 0.55 to 0.9 notches on the overall long-term credit rating at the end-2007. And, this effect increased to 0.8 to 1.23 notches by the end-2009 (Summary Table 8). At the end-2009, the effect of the government support is almost identical between the group of advanced countries and developing countries. Before the crisis, governments in advanced economies played a smaller role in boosting banks’ long-term ratings. These results are robust to a number of sample selection tests, such as testing for differential effects across developing and advanced countries, for both listed and non-listed banks, and also correcting for bank parental support and alternative estimations of an individual bank’s strength.

In interpreting these results, it is important to check if the averages mask large differences across countries. In fact, the overall rating bonuses in a section of large countries seem remarkably similar (Summary Table 9). For instance, mean support of Japanese banks was unchanged at 3.9 in 2007 and 2009. This implies, based on regressions without distinguishing advanced and developing countries, that overall ratings of systemically relevant banks profited by 2.9-3.5 notches from expected government support in 2007, with the value of this support increasing to 3.4-4.2 notches in 2009. For the top 45 U.S. banks, the mean support rating increased from 3.2 in 2007 to 4.1 in 2009. This translates into a 2.4-2.9 overall rating bonus for supported banks in 2007 and a much higher, 3.6-4.5, notch impact in 2009. In Germany, government support started high at 4.4 in 2007 and slightly increased to 4.6 in 2009. This suggests a 3.3-4.0 overall rating advantage of supported banks in 2007 and a 4.1-5.1 notch rating bonus in 2009.

For selected countries that have large banking centers and/or have been affected by the financial crisis, average government support ratings are about 3.6 in 2007 and 3.8 in 2009 on average (see Table 2, based on U.S. top 45 banks). Thus the overall rating bonuses for supported banks in this sample of countries are 2.7-3.2 in 2007 and 3.4-4.2 in 2009.

Our three-notch impact, on average, for advanced countries in 2007 is comparable to the results found by Soussa (2000) and Rimes (2005), although their studies are less rigorous and based on a smaller sample. In addition, Soussa (2000) reports structural annualized interest rate differentials among different credit ratings based on the average cumulative default rates (percent) for 1920-1999, calculated by Moody’s.17 According to his conversion table, when issuing a five-year bond, a three-notch rating increase translates into a funding advantage of 5 bp to 128 bp, depending on the riskiness of the institution.18 At the mid-point, it is 66.5 bp for a three-notch improvement, or 22bp for one-notch improvement. Using this and the overall rating bonuses described in the previous paragraph, we can evaluate the overall funding cost advantage of SIFIs as around 60bp in 2007 and 80bp in 2009.

This is helpful information, for example, if one would like to design a corrective levy on banks, which extracts the value of the subsidy. The funding cost advantage can be decomposed into the level of the government support and the time-varying risk premium. If a corrective levy were to be designed, it should not be affected by short-run market movements but should reflect only the long-run average value of rating bonuses, used here to calculate the total value of the structural government support. As discussed above, we find that the level of the structural government support has increased in most countries in 2009 compared to 2007. Still, we note that our estimate for the value of government support is lower than the real-time market value during crisis.

Our estimate may be also an overestimate of the required tax rate that would neutralize the (implicit) SIFI subsidy, since the competitive advantage of a guaranteed firm versus a nonguaranteed firm can be magnified (the former gains market share and the latter loses market share). One possibility is that the advantages and disadvantages are equally distributed between the two firms. Then, the levy rate that would eliminate the competitive distortion is smaller than the estimated difference in the funding costs. In this simple example, it would be half of the values given above. Nevertheless, the corrective tax required to correct the distortion of government support would remain sizable.

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

BCBS: Models and tools for macroprudential analysis

Models and tools for macroprudential analysis

BCBS Working Papers No 21

May 2012

The Basel Committee's Research Task Force Transmission Channel project aimed at generating new research on various aspects of the credit channel linkages in the monetary transmission mechanism. Under the credit channel view, financial intermediaries play a critical role in the allocation of credit in the economy. They are the primary source of credit for consumers and businesses that do not have direct access to capital markets. Among more traditional macroeconomic modelling approaches, the credit view is unique in its emphasis on the health of the financial sector as a critically important determinant of the efficacy of monetary policy.

The final products of the project are two working papers that summarise the findings of the many individual research projects that were undertaken and discussed in the course of the project. The first working paper, Basel Committee Working Paper No 20, "The policy implications of transmission channels between the financial system and the real economy", analyses the link between the real economy and the financial sector, and channels through which the financial system may transmit instability to the real economy. The second working paper, Basel Committee Working Paper No 21, "Models and tools for macroprudential analysis", focuses on the methodological progress and modelling advancements aimed at improving financial stability monitoring and the identification of systemic risk potential. Because both working papers are summaries, they touch only briefly on the results and methods of the individual research papers that were developed during the course of the project. Each working paper includes comprehensive references with information that will allow the interested reader to contact any of the individual authors and acquire the most up-to-date version of the research that was summarised in each of these working papers.

http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_wp21.htm

BCBS Working Papers No 21

May 2012

The Basel Committee's Research Task Force Transmission Channel project aimed at generating new research on various aspects of the credit channel linkages in the monetary transmission mechanism. Under the credit channel view, financial intermediaries play a critical role in the allocation of credit in the economy. They are the primary source of credit for consumers and businesses that do not have direct access to capital markets. Among more traditional macroeconomic modelling approaches, the credit view is unique in its emphasis on the health of the financial sector as a critically important determinant of the efficacy of monetary policy.

The final products of the project are two working papers that summarise the findings of the many individual research projects that were undertaken and discussed in the course of the project. The first working paper, Basel Committee Working Paper No 20, "The policy implications of transmission channels between the financial system and the real economy", analyses the link between the real economy and the financial sector, and channels through which the financial system may transmit instability to the real economy. The second working paper, Basel Committee Working Paper No 21, "Models and tools for macroprudential analysis", focuses on the methodological progress and modelling advancements aimed at improving financial stability monitoring and the identification of systemic risk potential. Because both working papers are summaries, they touch only briefly on the results and methods of the individual research papers that were developed during the course of the project. Each working paper includes comprehensive references with information that will allow the interested reader to contact any of the individual authors and acquire the most up-to-date version of the research that was summarised in each of these working papers.

http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_wp21.htm

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

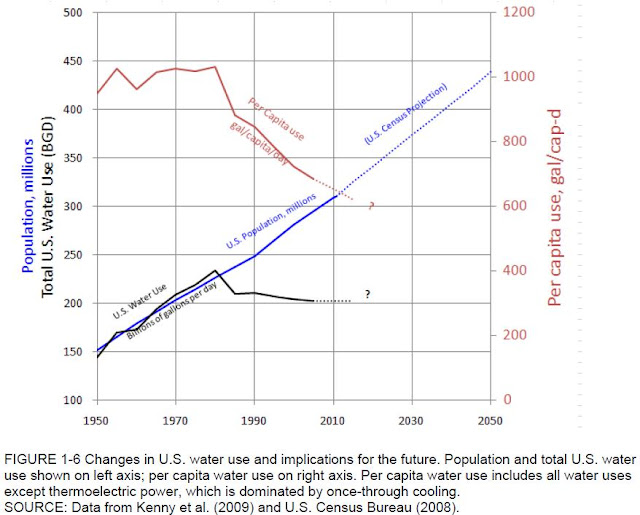

Changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future

It is interesting to see some data in Water Reuse: Expanding the Nation's Water Supply Through Reuse of Municipal Wastewater (http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13303), a National Research Council publication.

See for example figure 1-6, p 17, changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future:

See for example figure 1-6, p 17, changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future:

Monday, May 14, 2012

Do Dynamic Provisions Enhance Bank Solvency and Reduce Credit Procyclicality? A Study of the Chilean Banking System

Do Dynamic Provisions Enhance Bank Solvency and Reduce Credit Procyclicality? A Study of the Chilean Banking System. By Jorge A. Chan-Lau

IMF Working Paper No. 12/124

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25912.0

Summary: Dynamic provisions could help to enhance the solvency of individual banks and reduce procyclicality. Accomplishing these objectives depends on country-specific features of the banking system, business practices, and the calibration of the dynamic provisions scheme. In the case of Chile, a simulation analysis suggests Spanish dynamic provisions would improve banks' resilience to adverse shocks but would not reduce procyclicality. To address the latter, other countercyclical measures should be considered.

Excerpts

Introduction

It has long been acknowledged that procyclicality could pose risks to financial stability as noted by the academic and policy discussion centered on Basel II, accounting practices, and financial globalization. Recently, much attention has been focused on regulatory dynamic provisions (or statistical provisions). Under dynamic provisions, as banks build up their loan portfolio during an economic expansion, they should set aside provisions against future losses.

The use of dynamic provisions raises two questions bearing on financial stability. First, do dynamic provisions reduce insolvency risk? Second, do dynamic provisions reduce procyclicality? In theory the answer is yes to both questions. Provided loss estimates are roughly accurate, bank solvency is enhanced since buffers are built in advance ahead of the realization of large losses. Regulatory dynamic provisions could also discourage too rapid credit growth during the expansionary phase of the cycle, as it helps preventing a relaxation of provisioning practices.

However, when real data is brought to bear on the questions above the answers could diverge from what theory implies. This paper attempts to answer these questions in the specific case of Chile. It finds that the adoption of dynamic provisions could help to enhance bank solvency but it would not help to reduce procyclicality. The successful implementation of dynamic provisions, however, requires a careful calibration to match or exceed current provisioning practices, and it is worth noting that reliance on past data could lead to a false sense of security as loan losses are fat-tail events. Finally, since dynamic provisions may not be sufficient to counter procyclicality alternative measures should be considered, such as the proposed countercyclical capital buffers in Basel III and the countercyclical provision rule Peru implemented in 2008.

Conclusions

At the policy level, the case for regulatory dynamic provisions have been advanced on the grounds that they help reducing the risk of bank insolvency and dampening credit procyclicality. In the case of the Chile the data appears to partly validate these claims.

A simulation analysis suggests that under the Spanish dynamic provisions rule provision buffers against losses would be higher compared to those accumulated under current practices. The analysis also suggests that calibration based on historical data may not be adequate to deal with the presence of fat-tails in realized loan losses. Implementing dynamic provisions, therefore, requires a careful calibration of the regulatory model and stress testing loan-loss internal models.

Dynamic provision rules appear not to dampen procyclicality in Chile. Results from a VECM analysis indicate that the credit cycle does not respond to the level of or changes in aggregate provisions. In light of this result, it may be worth exploring other measures to address procyclicality. Two examples of these measures include countercyclical capital requirements, as proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010a and b), or the countercyclical provision rule introduced in Peru in 2008. The Basel countercyclical capital requirements suggest that the build up and release of additional capital buffers should be conditioned on deviations of credit to GDP ratio from its long-run trend. The Peruvian rule, contrary to standard dynamic provision rules, requires banks to accumulate countercyclical provisions when GDP growth exceeds potential. Both measures, by tying up capital or provision accumulations to cyclical indicators, could be more effective for reducing procyclicality.

IMF Working Paper No. 12/124

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25912.0

Summary: Dynamic provisions could help to enhance the solvency of individual banks and reduce procyclicality. Accomplishing these objectives depends on country-specific features of the banking system, business practices, and the calibration of the dynamic provisions scheme. In the case of Chile, a simulation analysis suggests Spanish dynamic provisions would improve banks' resilience to adverse shocks but would not reduce procyclicality. To address the latter, other countercyclical measures should be considered.

Excerpts

Introduction

It has long been acknowledged that procyclicality could pose risks to financial stability as noted by the academic and policy discussion centered on Basel II, accounting practices, and financial globalization. Recently, much attention has been focused on regulatory dynamic provisions (or statistical provisions). Under dynamic provisions, as banks build up their loan portfolio during an economic expansion, they should set aside provisions against future losses.

The use of dynamic provisions raises two questions bearing on financial stability. First, do dynamic provisions reduce insolvency risk? Second, do dynamic provisions reduce procyclicality? In theory the answer is yes to both questions. Provided loss estimates are roughly accurate, bank solvency is enhanced since buffers are built in advance ahead of the realization of large losses. Regulatory dynamic provisions could also discourage too rapid credit growth during the expansionary phase of the cycle, as it helps preventing a relaxation of provisioning practices.

However, when real data is brought to bear on the questions above the answers could diverge from what theory implies. This paper attempts to answer these questions in the specific case of Chile. It finds that the adoption of dynamic provisions could help to enhance bank solvency but it would not help to reduce procyclicality. The successful implementation of dynamic provisions, however, requires a careful calibration to match or exceed current provisioning practices, and it is worth noting that reliance on past data could lead to a false sense of security as loan losses are fat-tail events. Finally, since dynamic provisions may not be sufficient to counter procyclicality alternative measures should be considered, such as the proposed countercyclical capital buffers in Basel III and the countercyclical provision rule Peru implemented in 2008.

Conclusions

At the policy level, the case for regulatory dynamic provisions have been advanced on the grounds that they help reducing the risk of bank insolvency and dampening credit procyclicality. In the case of the Chile the data appears to partly validate these claims.

A simulation analysis suggests that under the Spanish dynamic provisions rule provision buffers against losses would be higher compared to those accumulated under current practices. The analysis also suggests that calibration based on historical data may not be adequate to deal with the presence of fat-tails in realized loan losses. Implementing dynamic provisions, therefore, requires a careful calibration of the regulatory model and stress testing loan-loss internal models.

Dynamic provision rules appear not to dampen procyclicality in Chile. Results from a VECM analysis indicate that the credit cycle does not respond to the level of or changes in aggregate provisions. In light of this result, it may be worth exploring other measures to address procyclicality. Two examples of these measures include countercyclical capital requirements, as proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010a and b), or the countercyclical provision rule introduced in Peru in 2008. The Basel countercyclical capital requirements suggest that the build up and release of additional capital buffers should be conditioned on deviations of credit to GDP ratio from its long-run trend. The Peruvian rule, contrary to standard dynamic provision rules, requires banks to accumulate countercyclical provisions when GDP growth exceeds potential. Both measures, by tying up capital or provision accumulations to cyclical indicators, could be more effective for reducing procyclicality.

Sunday, May 13, 2012

What Tokyo's Governor supporters think

A Japanese correspondant wrote about what Tokyo's Governor supporters think (edited):

I'll reply one of your questions about Tokyo's governor. He is a famous writer in Japan. Once in Japan, it was said "Money can move Politics." A leading politician who provided private funds to friends in politics, Tokyo's governor was once a lawmaker.

He gained funds by his writer activity, always speak radical statements since he was young, and he had been clearly different from other influential politicians. He was independent. He always strives to influence politicians with his great ability.

Thus, he was on the side of populace.

However he became arrogant now. But the Japanese people expect great things from him, in particular, people living in the capital, Tokyo. He always talks about "Changing Japan from Tokyo."

We think that he can do it.

Yours,

Nakaki

Friday, May 11, 2012

IMF Policy Papers: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low-Income Countries Series

IMF Policy Paper: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low-Income Countries - Background Paper

Summary: This note provides an overview of the literature on the challenges posed by shallow financial systems for macroeconomic policy implementation. Countries with shallow markets are more likely to choose fixed exchange rates, less likely to use indirect measures as instruments of monetary policy, and to implement effective counter-cyclical fiscal policies. But causation appears to work in both directions, as policy stances can themselves affect financial development. Drawing on recent FSAP reports, the note also shows that shallow financial markets tend to increase foreign exchange, liquidity management, and concentration risks, posing risks for financial stability

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4650

---

IMF Policy Paper: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillnace in Low-Income Countries - Financial Deepening and Macro-Stability

Summary: This paper aims to widen the lens through which surveillance is conducted in LICs, to better account for the interplay between financial deepening and macro-financial stability as called for in the 2011 Triennial Surveillance Review. Reflecting the inherent risk-return tradeoffs associated with financial deepening, the paper seeks to shed light on the policy and institutional impediments in LICs that have a bearing on the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies, macro-financial stability, and growth. The paper focuses attention on the role of enabling policies in facilitating sustainable financial deepening. In framing the discussion, the paper draws on a range of conceptual and analytical tools, empirical analyses, and case studies.

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4649

---

IMF Policy Paper: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low-Income Countries - Case Studies

Summary: This supplement presents ten case studies, which highlight the roles of targeted policies to facilitate sustainable financial deepening in a variety of country circumstances, reflecting historical experiences that parallel a range of markets in LICs. The case studies were selected to broadly capture efforts by countries to increase reach (e.g., financial inclusion), depth (e.g., financial intermediation), and breadth of financial systems (e.g., capital market, cross-border development). The analysis in the case studies highlights the importance of a balanced approach to financial deepening. A stable macroeconomic environment is vital to instill consumer, institutional, and investor confidence necessary to encourage financial market activity. Targeted public policy initiatives (e.g., collateral, payment systems development) can be helpful in removing impediments and creating infrastructure for improved market operations, while ensuring appropriate oversight and regulation of financial markets, to address potential sources of instability and market failures.

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4651

Summary: This note provides an overview of the literature on the challenges posed by shallow financial systems for macroeconomic policy implementation. Countries with shallow markets are more likely to choose fixed exchange rates, less likely to use indirect measures as instruments of monetary policy, and to implement effective counter-cyclical fiscal policies. But causation appears to work in both directions, as policy stances can themselves affect financial development. Drawing on recent FSAP reports, the note also shows that shallow financial markets tend to increase foreign exchange, liquidity management, and concentration risks, posing risks for financial stability

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4650

---

IMF Policy Paper: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillnace in Low-Income Countries - Financial Deepening and Macro-Stability

Summary: This paper aims to widen the lens through which surveillance is conducted in LICs, to better account for the interplay between financial deepening and macro-financial stability as called for in the 2011 Triennial Surveillance Review. Reflecting the inherent risk-return tradeoffs associated with financial deepening, the paper seeks to shed light on the policy and institutional impediments in LICs that have a bearing on the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies, macro-financial stability, and growth. The paper focuses attention on the role of enabling policies in facilitating sustainable financial deepening. In framing the discussion, the paper draws on a range of conceptual and analytical tools, empirical analyses, and case studies.

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4649

---

IMF Policy Paper: Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low-Income Countries - Case Studies

Summary: This supplement presents ten case studies, which highlight the roles of targeted policies to facilitate sustainable financial deepening in a variety of country circumstances, reflecting historical experiences that parallel a range of markets in LICs. The case studies were selected to broadly capture efforts by countries to increase reach (e.g., financial inclusion), depth (e.g., financial intermediation), and breadth of financial systems (e.g., capital market, cross-border development). The analysis in the case studies highlights the importance of a balanced approach to financial deepening. A stable macroeconomic environment is vital to instill consumer, institutional, and investor confidence necessary to encourage financial market activity. Targeted public policy initiatives (e.g., collateral, payment systems development) can be helpful in removing impediments and creating infrastructure for improved market operations, while ensuring appropriate oversight and regulation of financial markets, to address potential sources of instability and market failures.

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4651

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Some scholars argue that top rates can be raised drastically with no loss of revenue

Of Course 70% Tax Rates Are Counterproductive. By Alan Reynolds

Some scholars argue that top rates can be raised drastically with no loss of revenue. Their arguments are flawed.WSJ, May 7, 2012

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303916904577376041258476020.html

President Obama and others are demanding that we raise taxes on the "rich," and two recent academic papers that have gotten a lot of attention claim to show that there will be no ill effects if we do.

The first paper, by Peter Diamond of MIT and Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley, appeared in the Journal of Economic Perspectives last August. The second, by Mr. Saez, along with Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics and Stefanie Stantcheva of MIT, was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research three months later. Both suggested that federal tax revenues would not decline even if the rate on the top 1% of earners were raised to 73%-83%.

Can the apex of the Laffer Curve—which shows that the revenue-maximizing tax rate is not the highest possible tax rate—really be that high?

The authors arrive at their conclusion through an unusual calculation of the "elasticity" (responsiveness) of taxable income to changes in marginal tax rates. According to a formula devised by Mr. Saez, if the elasticity is 1.0, the revenue-maximizing top tax rate would be 40% including state and Medicare taxes. That means the elasticity of taxable income (ETI) would have to be an unbelievably low 0.2 to 0.25 if the revenue-maximizing top tax rates were 73%-83% for the top 1%. The authors of both papers reach this conclusion with creative, if wholly unpersuasive, statistical arguments.

Most of the older elasticity estimates are for all taxpayers, regardless of income. Thus a recent survey of 30 studies by the Canadian Department of Finance found that "The central ETI estimate in the international empirical literature is about 0.40."

But the ETI for all taxpayers is going to be lower than for higher-income earners, simply because people with modest incomes and modest taxes are not willing or able to vary their income much in response to small tax changes. So the real question is the ETI of the top 1%.

Harvard's Raj Chetty observed in 2009 that "The empirical literature on the taxable income elasticity has generally found that elasticities are large (0.5 to 1.5) for individuals in the top percentile of the income distribution." In that same year, Treasury Department economist Bradley Heim estimated that the ETI is 1.2 for incomes above $500,000 (the top 1% today starts around $350,000).

A 2010 study by Anthony Atkinson (Oxford) and Andrew Leigh (Australian National University) about changes in tax rates on the top 1% in five Anglo-Saxon countries came up with an ETI of 1.2 to 1.6. In a 2000 book edited by University of Michigan economist Joel Slemrod ("Does Atlas Shrug?"), Robert A. Moffitt (Johns Hopkins) and Mark Wilhelm (Indiana) estimated an elasticity of 1.76 to 1.99 for gross income. And at the bottom of the range, Mr. Saez in 2004 estimated an elasticity of 0.62 for gross income for the top 1%.

A midpoint between the estimates would be an elasticity for gross income of 1.3 for the top 1%, and presumably an even higher elasticity for taxable income (since taxpayers can claim larger deductions if tax rates go up.)

But let's stick with an ETI of 1.3 for the top 1%. This implies that the revenue-maximizing top marginal rate would be 33.9% for all taxes, and below 27% for the federal income tax.

To avoid reaching that conclusion, Messrs. Diamond and Saez's 2011 paper ignores all studies of elasticity among the top 1%, and instead chooses a midpoint of 0.25 between one uniquely low estimate of 0.12 for gross income among all taxpayers (from a 2004 study by Mr. Saez and Jonathan Gruber of MIT) and the 0.40 ETI norm from 30 other studies.

That made-up estimate of 0.25 is the sole basis for the claim by Messrs. Diamond and Saez in their 2011 paper that tax rates could reach 73% without losing revenue.

The Saez-Piketty-Stantcheva paper does not confound a lowball estimate for all taxpayers with a midpoint estimate for the top 1%. On the contrary, the authors say that "the long-run total elasticity of top incomes with respect to the net-of-tax rate is large."

Nevertheless, to cut this "large" elasticity down, the authors begin by combining the U.S. with 17 other affluent economies, telling us that elasticity estimates for top incomes are lower for Europe and Japan. The resulting mélange—an 18-country "overall elasticity of around 0.5"—has zero relevance to U.S. tax policy.

Still, it is twice as large as the ETI of Messrs. Diamond and Saez, so the three authors appear compelled to further pare their 0.5 estimate down to 0.2 in order to predict a "socially optimal" top tax rate of 83%. Using "admittedly only suggestive" evidence, they assert that only 0.2 of their 0.5 ETI can be attributed to real supply-side responses to changes in tax rates.

The other three-fifths of ETI can just be ignored, according to Messrs. Saez and Piketty, and Ms. Stantcheva, because it is the result of, among other factors, easily-plugged tax loopholes resulting from lower rates on corporations and capital gains.

Plugging these so-called loopholes, they say, requires "aligning the tax rates on realized capital gains with those on ordinary income" and enacting "neutrality in the effective tax rates across organizational forms." In plain English: Tax rates on U.S. corporate profits, dividends and capital gains must also be 83%.

This raises another question: At that level, would there be any profits, capital gains or top incomes left to tax?

"The optimal top tax," the three authors also say, "actually goes to 100% if the real supply-side elasticity is very small." If anyone still imagines the proposed "socially optimal" tax rates of 73%-83% on the top 1% would raise revenues and have no effect on economic growth, what about that 100% rate?

Mr. Reynolds is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute and the author of "Income and Wealth" (Greenwood Press, 2006).

Some scholars argue that top rates can be raised drastically with no loss of revenue. Their arguments are flawed.WSJ, May 7, 2012

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303916904577376041258476020.html

President Obama and others are demanding that we raise taxes on the "rich," and two recent academic papers that have gotten a lot of attention claim to show that there will be no ill effects if we do.

The first paper, by Peter Diamond of MIT and Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley, appeared in the Journal of Economic Perspectives last August. The second, by Mr. Saez, along with Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics and Stefanie Stantcheva of MIT, was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research three months later. Both suggested that federal tax revenues would not decline even if the rate on the top 1% of earners were raised to 73%-83%.

Can the apex of the Laffer Curve—which shows that the revenue-maximizing tax rate is not the highest possible tax rate—really be that high?

The authors arrive at their conclusion through an unusual calculation of the "elasticity" (responsiveness) of taxable income to changes in marginal tax rates. According to a formula devised by Mr. Saez, if the elasticity is 1.0, the revenue-maximizing top tax rate would be 40% including state and Medicare taxes. That means the elasticity of taxable income (ETI) would have to be an unbelievably low 0.2 to 0.25 if the revenue-maximizing top tax rates were 73%-83% for the top 1%. The authors of both papers reach this conclusion with creative, if wholly unpersuasive, statistical arguments.

Most of the older elasticity estimates are for all taxpayers, regardless of income. Thus a recent survey of 30 studies by the Canadian Department of Finance found that "The central ETI estimate in the international empirical literature is about 0.40."

But the ETI for all taxpayers is going to be lower than for higher-income earners, simply because people with modest incomes and modest taxes are not willing or able to vary their income much in response to small tax changes. So the real question is the ETI of the top 1%.

Harvard's Raj Chetty observed in 2009 that "The empirical literature on the taxable income elasticity has generally found that elasticities are large (0.5 to 1.5) for individuals in the top percentile of the income distribution." In that same year, Treasury Department economist Bradley Heim estimated that the ETI is 1.2 for incomes above $500,000 (the top 1% today starts around $350,000).

A 2010 study by Anthony Atkinson (Oxford) and Andrew Leigh (Australian National University) about changes in tax rates on the top 1% in five Anglo-Saxon countries came up with an ETI of 1.2 to 1.6. In a 2000 book edited by University of Michigan economist Joel Slemrod ("Does Atlas Shrug?"), Robert A. Moffitt (Johns Hopkins) and Mark Wilhelm (Indiana) estimated an elasticity of 1.76 to 1.99 for gross income. And at the bottom of the range, Mr. Saez in 2004 estimated an elasticity of 0.62 for gross income for the top 1%.

A midpoint between the estimates would be an elasticity for gross income of 1.3 for the top 1%, and presumably an even higher elasticity for taxable income (since taxpayers can claim larger deductions if tax rates go up.)

But let's stick with an ETI of 1.3 for the top 1%. This implies that the revenue-maximizing top marginal rate would be 33.9% for all taxes, and below 27% for the federal income tax.

To avoid reaching that conclusion, Messrs. Diamond and Saez's 2011 paper ignores all studies of elasticity among the top 1%, and instead chooses a midpoint of 0.25 between one uniquely low estimate of 0.12 for gross income among all taxpayers (from a 2004 study by Mr. Saez and Jonathan Gruber of MIT) and the 0.40 ETI norm from 30 other studies.

That made-up estimate of 0.25 is the sole basis for the claim by Messrs. Diamond and Saez in their 2011 paper that tax rates could reach 73% without losing revenue.

The Saez-Piketty-Stantcheva paper does not confound a lowball estimate for all taxpayers with a midpoint estimate for the top 1%. On the contrary, the authors say that "the long-run total elasticity of top incomes with respect to the net-of-tax rate is large."

Nevertheless, to cut this "large" elasticity down, the authors begin by combining the U.S. with 17 other affluent economies, telling us that elasticity estimates for top incomes are lower for Europe and Japan. The resulting mélange—an 18-country "overall elasticity of around 0.5"—has zero relevance to U.S. tax policy.

Still, it is twice as large as the ETI of Messrs. Diamond and Saez, so the three authors appear compelled to further pare their 0.5 estimate down to 0.2 in order to predict a "socially optimal" top tax rate of 83%. Using "admittedly only suggestive" evidence, they assert that only 0.2 of their 0.5 ETI can be attributed to real supply-side responses to changes in tax rates.

The other three-fifths of ETI can just be ignored, according to Messrs. Saez and Piketty, and Ms. Stantcheva, because it is the result of, among other factors, easily-plugged tax loopholes resulting from lower rates on corporations and capital gains.

Plugging these so-called loopholes, they say, requires "aligning the tax rates on realized capital gains with those on ordinary income" and enacting "neutrality in the effective tax rates across organizational forms." In plain English: Tax rates on U.S. corporate profits, dividends and capital gains must also be 83%.

This raises another question: At that level, would there be any profits, capital gains or top incomes left to tax?

"The optimal top tax," the three authors also say, "actually goes to 100% if the real supply-side elasticity is very small." If anyone still imagines the proposed "socially optimal" tax rates of 73%-83% on the top 1% would raise revenues and have no effect on economic growth, what about that 100% rate?

Mr. Reynolds is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute and the author of "Income and Wealth" (Greenwood Press, 2006).

Bank Capitalization as a Signal. By Daniel C. Hardy

Bank Capitalization as a Signal. By Daniel C. Hardy

IMF Working Paper No. 12/114

May 2012

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25894.0

Summary: The level of a bank‘s capitalization can effectively transmit information about its riskiness and therefore support market discipline, but asymmetry information may induce exaggerated or distortionary behavior: banks may vie with one another to signal confidence in their prospects by keeping capitalization low, and banks‘ creditors often cannot distinguish among them - tendencies that can be seen across banks and across time. Prudential policy is warranted to help offset these tendencies.

IMF Working Paper No. 12/114

May 2012

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25894.0

Summary: The level of a bank‘s capitalization can effectively transmit information about its riskiness and therefore support market discipline, but asymmetry information may induce exaggerated or distortionary behavior: banks may vie with one another to signal confidence in their prospects by keeping capitalization low, and banks‘ creditors often cannot distinguish among them - tendencies that can be seen across banks and across time. Prudential policy is warranted to help offset these tendencies.

Friday, May 4, 2012

Women, Welch Clash at Forum - "Great women get upset about getting into the victim's unit"

Women, Welch Clash at Forum. By John Bussey

Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2012, page B1

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303877604577382321364803912.html

Is Jack Welch a timeless seer or an out-of-touch warhorse?

The former Master and Commander of General Electric still writes widely on business strategy. He's also influential on the speaking circuit.

On Wednesday, Mr. Welch and his wife and writing partner, Suzy Welch, told a gathering of women executives from a range of industries that, in matters of career track, it is results and performance that chart the way. Programs promoting diversity, mentorships and affinity groups may or may not be good, but they are not how women get ahead. "Over deliver," Mr. Welch advised. "Performance is it!"

Angry murmurs ran through the crowd. The speakers asked: Were there any questions?

"We're regaining our consciousness," one woman executive shot back.

Mr. Welch had walked into a spinning turbine fan blade.

"Of course women need to perform to advance," Alison Quirk, an executive vice president at the investment firm State Street Corp., said later. "But we can all do more to help people understand their unconscious biases."

"He showed no recognition that the culture shapes the performance metrics, and the culture is that of white men," another executive said.

Academy Award winning actor Geena Davis talks about the perception of women as seen in the media and about what has and has not changed in the past sixty years.

Dee Dee Myers, a former White House press secretary who is now with Glover Park Group, a communications firm, added: "While he seemed to acknowledge the value of a diverse workforce, he didn't seem to think it was necessary to develop strategies for getting there—and especially for taking a cold, hard look at some of the subtle barriers to women's advancement that still exist. If objective performance measures were enough, more than a handful of Fortune 500 senior executives would already be women. "

"This meritocracy fiction may be the single biggest obstacle to women's advancement," added Lisa Levey, a consultant who heard Mr. Welch speak.

Mr. Welch has sparked controversy in the past with his view of the workplace. In 2009, he told a group of human-resources managers: "There's no such thing as work-life balance." Instead, "there are work-life choices, and you make them, and they have consequences." Step out of the arena to raise kids, and don't be surprised if the promotion passes you by.

Of the Fortune 500 companies, only 3% have a female CEO today. Female board membership is similarly spare. A survey of 60 major companies by McKinsey shows women occupying 53% of entry-level positions, 40% of manager positions, and only 19% of C-suite jobs.

The reasons for this are complex and aren't always about child rearing. A separate McKinsey survey showed that among women who have already reached the status of successful executive, 59% don't aspire to one of the top jobs. The majority of these women have already had children.

"Their work ethic—these people are doing it all," said Dominic Barton of McKinsey. "They say, 'I'm the person turning off the lights'" at the end of the day.

Instead, Mr. Barton said, it's "the soft stuff, the culture" that's shaping their career decisions.

The group of women executives who wrestled with Mr. Welch were at a conference on Women in the Economy held by The Wall Street Journal this week. Among other things, they tackled the culture questions—devising strategies to get more high-performing women to the top, keep women on track during childbearing years, address bias, and make the goals of diversity motivating to employees. They also discussed the sexual harassment some women still experience in the workplace. (A report on the group's findings will be published in the Journal Monday.)

The realm of the "soft stuff" may not be Mr. Welch's favored zone. During his remarks, he referred to human resources as "the H.R. teams that are out there, most of them for birthdays and picnics." He mentioned a women's forum inside GE that he says attracted 500 participants. "The best of the women would come to me and say, 'I don't want to be in a special group. I'm not in the victim's unit. I'm a star. I want to be compared with the best of your best.'"

And then he addressed the audience: "Stop lying about it. It's true. Great women get upset about getting into the victim's unit."

Individual mentoring programs, meanwhile, are "one of the worst ideas that ever came along," he said. "You should see everyone as a mentor."

He had this advice for women who want to get ahead: Grab tough assignments to prove yourself, get line experience, and embrace serious performance reviews and the coaching inherent in them.

"Without a rigorous appraisal system, without you knowing where you stand...and how you can improve, none of these 'help' programs that were up there are going to be worth much to you," he said. Mr. Welch said later that the appraisal "is the best way to attack bias" because the facts go into the document, which both parties have to sign.

Mr. Welch championed the business philosophy of "Six Sigma" at GE, a strategy that seeks to expunge defects from production through constant review and improvement. It appears to work with machines and business processes.

But applying that clinical procedure to the human character, as Mr. Welch seems to want to do, is a stickier proposition.

"His advice was not tailored to how women can attain parity in today's male-dominated workplace," said one female board member of a Fortune 500 company. Indeed, a couple of women walked out in frustration during his presentation.

Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2012, page B1

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303877604577382321364803912.html

Is Jack Welch a timeless seer or an out-of-touch warhorse?

The former Master and Commander of General Electric still writes widely on business strategy. He's also influential on the speaking circuit.

On Wednesday, Mr. Welch and his wife and writing partner, Suzy Welch, told a gathering of women executives from a range of industries that, in matters of career track, it is results and performance that chart the way. Programs promoting diversity, mentorships and affinity groups may or may not be good, but they are not how women get ahead. "Over deliver," Mr. Welch advised. "Performance is it!"

Angry murmurs ran through the crowd. The speakers asked: Were there any questions?

"We're regaining our consciousness," one woman executive shot back.

Mr. Welch had walked into a spinning turbine fan blade.

"Of course women need to perform to advance," Alison Quirk, an executive vice president at the investment firm State Street Corp., said later. "But we can all do more to help people understand their unconscious biases."

"He showed no recognition that the culture shapes the performance metrics, and the culture is that of white men," another executive said.

Academy Award winning actor Geena Davis talks about the perception of women as seen in the media and about what has and has not changed in the past sixty years.

Dee Dee Myers, a former White House press secretary who is now with Glover Park Group, a communications firm, added: "While he seemed to acknowledge the value of a diverse workforce, he didn't seem to think it was necessary to develop strategies for getting there—and especially for taking a cold, hard look at some of the subtle barriers to women's advancement that still exist. If objective performance measures were enough, more than a handful of Fortune 500 senior executives would already be women. "

"This meritocracy fiction may be the single biggest obstacle to women's advancement," added Lisa Levey, a consultant who heard Mr. Welch speak.

Mr. Welch has sparked controversy in the past with his view of the workplace. In 2009, he told a group of human-resources managers: "There's no such thing as work-life balance." Instead, "there are work-life choices, and you make them, and they have consequences." Step out of the arena to raise kids, and don't be surprised if the promotion passes you by.

Of the Fortune 500 companies, only 3% have a female CEO today. Female board membership is similarly spare. A survey of 60 major companies by McKinsey shows women occupying 53% of entry-level positions, 40% of manager positions, and only 19% of C-suite jobs.

The reasons for this are complex and aren't always about child rearing. A separate McKinsey survey showed that among women who have already reached the status of successful executive, 59% don't aspire to one of the top jobs. The majority of these women have already had children.

"Their work ethic—these people are doing it all," said Dominic Barton of McKinsey. "They say, 'I'm the person turning off the lights'" at the end of the day.

Instead, Mr. Barton said, it's "the soft stuff, the culture" that's shaping their career decisions.

The group of women executives who wrestled with Mr. Welch were at a conference on Women in the Economy held by The Wall Street Journal this week. Among other things, they tackled the culture questions—devising strategies to get more high-performing women to the top, keep women on track during childbearing years, address bias, and make the goals of diversity motivating to employees. They also discussed the sexual harassment some women still experience in the workplace. (A report on the group's findings will be published in the Journal Monday.)

The realm of the "soft stuff" may not be Mr. Welch's favored zone. During his remarks, he referred to human resources as "the H.R. teams that are out there, most of them for birthdays and picnics." He mentioned a women's forum inside GE that he says attracted 500 participants. "The best of the women would come to me and say, 'I don't want to be in a special group. I'm not in the victim's unit. I'm a star. I want to be compared with the best of your best.'"

And then he addressed the audience: "Stop lying about it. It's true. Great women get upset about getting into the victim's unit."

Individual mentoring programs, meanwhile, are "one of the worst ideas that ever came along," he said. "You should see everyone as a mentor."

He had this advice for women who want to get ahead: Grab tough assignments to prove yourself, get line experience, and embrace serious performance reviews and the coaching inherent in them.

"Without a rigorous appraisal system, without you knowing where you stand...and how you can improve, none of these 'help' programs that were up there are going to be worth much to you," he said. Mr. Welch said later that the appraisal "is the best way to attack bias" because the facts go into the document, which both parties have to sign.

Mr. Welch championed the business philosophy of "Six Sigma" at GE, a strategy that seeks to expunge defects from production through constant review and improvement. It appears to work with machines and business processes.

But applying that clinical procedure to the human character, as Mr. Welch seems to want to do, is a stickier proposition.

"His advice was not tailored to how women can attain parity in today's male-dominated workplace," said one female board member of a Fortune 500 company. Indeed, a couple of women walked out in frustration during his presentation.

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Dynamic Loan Loss Provisioning: Simulations on Effectiveness and Guide to Implementation

Dynamic Loan Loss Provisioning: Simulations on Effectiveness and Guide to Implementation. By Torsten Wezel, Jorge A. Chan Lau, and Francesco Columba

IMF Working Paper No. 12/110

May 01, 2012

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25885.0

Summary: This simulation-based paper investigates the impact of different methods of dynamic provisioning on bank soundness and shows that this increasingly popular macroprudential tool can smooth provisioning costs over the credit cycle and lower banks’ probability of default. In additon, the paper offers an in-depth guide to implementation that addresses pertinent issues related to data requirements, calibration and safeguards as well as accounting, disclosure and tax treatment. It also discusses the interaction of dynamic provisioning with other macroprudential instruments such as countercyclical capital.

Excerpts:

Introduction

Reducing the procyclicality of the banking sector by way of macroprudential policy instruments has become a policy priority. The recent crisis has illustrated how excessive procyclicality of the banking system may activate powerful macro-financial linkages that amplify the business cycle and how increased financial instability can have large negative spillover effects onto the real sector. Moreover, research has shown that crises that included banking turmoil are among the longest and most severe of all crises.

Although there is no consensus yet on the very definition of macroprudential policy, an array of such tools, especially those of countercyclical nature, has been applied in many countries for years. But it was only during the financial crisis that powerful macro-financial linkages played out on a global scale, conveying a sense of urgency.

In the wake of the crisis, policymakers therefore intensified their efforts to gear the macroprudential approach to financial stability towards improving banks’ capacity to absorb shocks—a consultative process that culminated in the development of the Basel III framework in December 2010 to be phased in over the coming years. In addition to improving the quality of bank capital and liquidity as well as imposing a minimum leverage ratio, this new regulatory standard introduces countercyclical capital buffers and lends support to forward-looking loan loss provisioning, which comprises dynamic provisioning (DP).

The new capital standard promotes the build-up of capital buffers in good times that can be drawn down in periods of stress, in the form of a capital conservation requirement to increase the banking sector’s resilience entering into a downturn. Part of this conservation buffer would be a countercyclical buffer that is to be activated only when there is excess credit growth so that the sector is not destabilized in the downturn. Such countercyclical capital has also been characterized as potentially cushioning the economy’s real output during a crisis (IMF, 2011). Similarly, dynamic provisioning requires banks to build a cushion of generic provisions during an upswing that can be used to cover rising specific provisions linked to loan delinquencies during the subsequent downturn.

Both countercyclical capital and DP have been applied in practice. Some countries have adjusted capital regulations in different phases of the cycle to give them a more potent countercyclical impact: Brazil has used a formula to smooth capital requirements for interest rate risk in times of extreme volatility, China introduced a countercyclical capital requirement similar to the countercyclical buffer under Basel III, and India has made countercyclical adjustments in risk weights and in provisioning. DP was first introduced by Spain in 2000 and subsequently adopted in Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia, while other countries such as Mexico and Chile switched to provisioning based on expected loan loss. Peru is the only country to explicitly use both countercyclical instruments in combination.

The concept of DP examined in this paper is intriguing. By gradually building a countercyclical loan loss reserve in good times and then using it to cover losses as they arise in bad times, DP is able to greatly smooth provisioning costs over the cycle and thus insulate banks’ profit and loss statements in this regard. Therefore, DP may usefully complement other policies targeted more at macroeconomic aggregates. The implementation of DP can, however, be a delicate balancing exercise. The calibration is typically challenging because it requires specific data, and even if these are available, it may still be inaccurate if the subsequent credit cycle differs substantially from the previous one(s) on which the model is necessarily predicated. Over-provisioning may ensue in particular instances. This said, a careful calibration that tries to incorporate as many of the stylized facts of past credit developments as possible goes a long way in providing a sizeable cushion for banks to withstand periodic downswings.

This paper provides strong support for DP as a tool for countercyclical banking policies. Our contribution to this strand of the literature is threefold. We first recreate a hypothetical path of provisions under different DP systems based on historical data of an emerging banking market and compare the outcome to the actual situation without DP. These counterfactual simulations suggest that a well-calibrated system of DP mitigates procyclicality in provisioning costs and thus earnings and capital. Second, using Monte-Carlo simulations we show that the countercyclical buffer that DP builds typically lowers a bank’s probability of default. Finally, we offer a guide to implementation of the DP concept that seeks to clarify issues related to data requirements, choice of formula, parametrization, accounting treatment, and recalibration.

Other studies that have used counterfactual simulations based on historical data to assess the hypothetical performance under DP include Balla and McKenna (2009), Fillat and Montoriol- Garriga (2010), both using U.S. bank data, and Wezel (2010), using data for Uruguay. All studies find support for the notion that DP, when properly calibrated, can help absorb rising loan losses in a downturn and thus be a useful macroprudential tool in this regard. Some other studies (Lim et al., 2011; Peydró-Alcalde et al., 2011) even find that DP is effective in mitigating swings in credit growth, although this should not be expected of DP in general.

Conclusion

This paper has provided a thorough analysis of the merits and challenges associated with dynamic provisioning—a macroprudential tool that deserves attention from policymakers and regulators for its capacity to distribute the burden of loan impairment evenly over the credit cycle and so quench an important source of procyclicality in banking. Our simulations that apply the Spanish and Peruvian DP formulas to a full cycle of banking data of an advanced emerging market leave little doubt that the countercyclical buffer built under DP not only smoothes costs but actually bolsters financial stability by lowering banks’ PD in severe downturn conditions. We also show that for best countercyclical results DP should be tailored to the different risk exposures of individual banks and the specific circumstances of banking sectors, presenting measures such as bank-specific rates or hybrid systems combining the virtues of formulas.

While the simple concept of providing in good times for lean years is intuitive, it has its operational challenges. When calibrating a DP system great care must be taken to keep countercyclical reserves in line with expected loan losses and so avoid insufficient buffers or excessive coverage. As many of the features and needed restrictions are not easily understood or operationalized, we offer a comprehensive primer for regulators eager to implement one of the variants of DP analyzed in the paper. The discussion of practical challenges also includes thorny issues like compliance with accounting standards. In fact, policymakers have long tended to dismiss DP on grounds that it is not legitimate from an accounting perspective and therefore focused on other tools such as countercyclical capital. To remedy this problem, we propose ways to recalibrate the formula periodically and so keep it in line with expected loan loss. Further, while recognizing that countercyclical capital has its definite place in the macroprudential toolkit, we argue that DP acts as a first line of defense by directly shielding bank profits, thereby lowering the degree to which other countercyclical instruments are needed. However, there should be no doubt that due to the limited impact of DP in restraining excessive credit growth complacency in supervision due to DP buffers should be avoided and that DP needs to be accompanied by other macroprudential tools aimed at mitigating particular systemic risks.

Clearly, further research is needed on the interaction between DP and countercyclical capital as well as other macroprudential tools to answer the question in what ways they can complement one another in providing an integrated countercyclical buffer. As an early example, Saurina (2011) analyzes DP and countercyclical capital side-by-side but not their possible interaction. Another area of needed research is the impact of DP on credit cycles and other macroeconomic aggregates. Newer studies (e.g., Peydró-Alcalde et al., 2011; Chan-Lau, 2012) evaluate the implications of DP for credit availability, yet broader-based results are certainly warranted. The ongoing efforts by a number of countries towards adopting DP systems and other forms of forward-looking provisioning will provide a fertile ground for such future research.

IMF Working Paper No. 12/110

May 01, 2012

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25885.0

Summary: This simulation-based paper investigates the impact of different methods of dynamic provisioning on bank soundness and shows that this increasingly popular macroprudential tool can smooth provisioning costs over the credit cycle and lower banks’ probability of default. In additon, the paper offers an in-depth guide to implementation that addresses pertinent issues related to data requirements, calibration and safeguards as well as accounting, disclosure and tax treatment. It also discusses the interaction of dynamic provisioning with other macroprudential instruments such as countercyclical capital.

Excerpts:

Introduction

Reducing the procyclicality of the banking sector by way of macroprudential policy instruments has become a policy priority. The recent crisis has illustrated how excessive procyclicality of the banking system may activate powerful macro-financial linkages that amplify the business cycle and how increased financial instability can have large negative spillover effects onto the real sector. Moreover, research has shown that crises that included banking turmoil are among the longest and most severe of all crises.

Although there is no consensus yet on the very definition of macroprudential policy, an array of such tools, especially those of countercyclical nature, has been applied in many countries for years. But it was only during the financial crisis that powerful macro-financial linkages played out on a global scale, conveying a sense of urgency.

In the wake of the crisis, policymakers therefore intensified their efforts to gear the macroprudential approach to financial stability towards improving banks’ capacity to absorb shocks—a consultative process that culminated in the development of the Basel III framework in December 2010 to be phased in over the coming years. In addition to improving the quality of bank capital and liquidity as well as imposing a minimum leverage ratio, this new regulatory standard introduces countercyclical capital buffers and lends support to forward-looking loan loss provisioning, which comprises dynamic provisioning (DP).

The new capital standard promotes the build-up of capital buffers in good times that can be drawn down in periods of stress, in the form of a capital conservation requirement to increase the banking sector’s resilience entering into a downturn. Part of this conservation buffer would be a countercyclical buffer that is to be activated only when there is excess credit growth so that the sector is not destabilized in the downturn. Such countercyclical capital has also been characterized as potentially cushioning the economy’s real output during a crisis (IMF, 2011). Similarly, dynamic provisioning requires banks to build a cushion of generic provisions during an upswing that can be used to cover rising specific provisions linked to loan delinquencies during the subsequent downturn.

Both countercyclical capital and DP have been applied in practice. Some countries have adjusted capital regulations in different phases of the cycle to give them a more potent countercyclical impact: Brazil has used a formula to smooth capital requirements for interest rate risk in times of extreme volatility, China introduced a countercyclical capital requirement similar to the countercyclical buffer under Basel III, and India has made countercyclical adjustments in risk weights and in provisioning. DP was first introduced by Spain in 2000 and subsequently adopted in Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia, while other countries such as Mexico and Chile switched to provisioning based on expected loan loss. Peru is the only country to explicitly use both countercyclical instruments in combination.

The concept of DP examined in this paper is intriguing. By gradually building a countercyclical loan loss reserve in good times and then using it to cover losses as they arise in bad times, DP is able to greatly smooth provisioning costs over the cycle and thus insulate banks’ profit and loss statements in this regard. Therefore, DP may usefully complement other policies targeted more at macroeconomic aggregates. The implementation of DP can, however, be a delicate balancing exercise. The calibration is typically challenging because it requires specific data, and even if these are available, it may still be inaccurate if the subsequent credit cycle differs substantially from the previous one(s) on which the model is necessarily predicated. Over-provisioning may ensue in particular instances. This said, a careful calibration that tries to incorporate as many of the stylized facts of past credit developments as possible goes a long way in providing a sizeable cushion for banks to withstand periodic downswings.

This paper provides strong support for DP as a tool for countercyclical banking policies. Our contribution to this strand of the literature is threefold. We first recreate a hypothetical path of provisions under different DP systems based on historical data of an emerging banking market and compare the outcome to the actual situation without DP. These counterfactual simulations suggest that a well-calibrated system of DP mitigates procyclicality in provisioning costs and thus earnings and capital. Second, using Monte-Carlo simulations we show that the countercyclical buffer that DP builds typically lowers a bank’s probability of default. Finally, we offer a guide to implementation of the DP concept that seeks to clarify issues related to data requirements, choice of formula, parametrization, accounting treatment, and recalibration.

Other studies that have used counterfactual simulations based on historical data to assess the hypothetical performance under DP include Balla and McKenna (2009), Fillat and Montoriol- Garriga (2010), both using U.S. bank data, and Wezel (2010), using data for Uruguay. All studies find support for the notion that DP, when properly calibrated, can help absorb rising loan losses in a downturn and thus be a useful macroprudential tool in this regard. Some other studies (Lim et al., 2011; Peydró-Alcalde et al., 2011) even find that DP is effective in mitigating swings in credit growth, although this should not be expected of DP in general.

Conclusion

This paper has provided a thorough analysis of the merits and challenges associated with dynamic provisioning—a macroprudential tool that deserves attention from policymakers and regulators for its capacity to distribute the burden of loan impairment evenly over the credit cycle and so quench an important source of procyclicality in banking. Our simulations that apply the Spanish and Peruvian DP formulas to a full cycle of banking data of an advanced emerging market leave little doubt that the countercyclical buffer built under DP not only smoothes costs but actually bolsters financial stability by lowering banks’ PD in severe downturn conditions. We also show that for best countercyclical results DP should be tailored to the different risk exposures of individual banks and the specific circumstances of banking sectors, presenting measures such as bank-specific rates or hybrid systems combining the virtues of formulas.

While the simple concept of providing in good times for lean years is intuitive, it has its operational challenges. When calibrating a DP system great care must be taken to keep countercyclical reserves in line with expected loan losses and so avoid insufficient buffers or excessive coverage. As many of the features and needed restrictions are not easily understood or operationalized, we offer a comprehensive primer for regulators eager to implement one of the variants of DP analyzed in the paper. The discussion of practical challenges also includes thorny issues like compliance with accounting standards. In fact, policymakers have long tended to dismiss DP on grounds that it is not legitimate from an accounting perspective and therefore focused on other tools such as countercyclical capital. To remedy this problem, we propose ways to recalibrate the formula periodically and so keep it in line with expected loan loss. Further, while recognizing that countercyclical capital has its definite place in the macroprudential toolkit, we argue that DP acts as a first line of defense by directly shielding bank profits, thereby lowering the degree to which other countercyclical instruments are needed. However, there should be no doubt that due to the limited impact of DP in restraining excessive credit growth complacency in supervision due to DP buffers should be avoided and that DP needs to be accompanied by other macroprudential tools aimed at mitigating particular systemic risks.

Clearly, further research is needed on the interaction between DP and countercyclical capital as well as other macroprudential tools to answer the question in what ways they can complement one another in providing an integrated countercyclical buffer. As an early example, Saurina (2011) analyzes DP and countercyclical capital side-by-side but not their possible interaction. Another area of needed research is the impact of DP on credit cycles and other macroeconomic aggregates. Newer studies (e.g., Peydró-Alcalde et al., 2011; Chan-Lau, 2012) evaluate the implications of DP for credit availability, yet broader-based results are certainly warranted. The ongoing efforts by a number of countries towards adopting DP systems and other forms of forward-looking provisioning will provide a fertile ground for such future research.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

Pharma: New Tufts Report Shows Academic-Industry Partnerships Are Mutually Beneficial

| New Tufts Report Shows Academic-Industry Partnerships Are Mutually Beneficial |

http://www.innovation.org/index.cfm/NewsCenter/Newsletters?NID=200

April 30, 2012 -