Social Media and Well-Being: Pitfalls, Progress, and Next Steps. Ethan Kross et al. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, November 10 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.005

Rolf Degen's take: https://twitter.com/DegenRolf/status/1326180998074273797

Highlights

- Social media has revolutionized how humans interact, providing them with unprecedented opportunities to satisfy their social needs.

- An explosion of research has examined whether social media impacts well-being. First- and second-generation studies examining this issue yielded inconsistent results.

- An emerging set of third-generation experiments has begun to reveal small but significant negative effects of overall social media use on well-being.

- The results of these experiments mask the complexities characterizing the relationship between social media and well-being. Whether it enhances or diminishes well-being depends on how and why people use it, as well as who uses it.

- People use social media for different reasons (e.g., to manage impressions, to share emotions), which influence how it impacts their own and other people’s well-being.

Abstract: Within a relatively short time span, social media have transformed the way humans interact, leading many to wonder what, if any, implications this interactive revolution has had for people’s emotional lives. Over the past 15 years, an explosion of research has examined this issue, generating countless studies and heated debate. Although early research generated inconclusive findings, several experiments have revealed small negative effects of social media use on well-being. These results mask, however, a deeper set of complexities. Accumulating evidence indicates that social media can enhance or diminish well-being depending on how people use them. Future research is needed to model these complexities using stronger methods to advance knowledge in this domain.

Keywords: social mediaFacebookwell-beingonline social networksemotionlife satisfaction

Moving Forward

We have drawn multiple parallels between the printing press and social media in this review, but there is one notable difference. Whereas the printing press took decades to revolutionize the way society functioned, social media have had a transformational impact in a tiny window of time. Nevertheless, scientists have been remarkably nimble in their ability to reroute their research programs to respond to the challenge of making sense of how this technology impacts people’s emotional lives. Indeed, we view the past 15 years of research on social media and well-being as a testament to scientists doing what they do best: focusing on important phenomena, critically evaluating current knowledge in light of new results, and bringing to bear increasingly sophisticated methods and conceptual frameworks to generate novel solutions that have important basic science and practical implications. But where does all of this work leave us in terms of the question on so many people’s minds: how do social media influence well-being?

Converging reviews of the literature suggest that a small but significant negative relationship characterizes the effect of social media on well-being (Box 3). If this is all that one cares about, that is the bird’s eye view. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude from these findings that social media have little potential to influence people’s emotional lives. Our survey suggests that the situation concerning social media’s impact on well-being is considerably more nuanced than aggregate usage studies suggest. The effects of social media on well-being are not uniform. Social media present people with a new ecosystem for engaging in social interactions, and converging evidence indicates that how this ecosystem affects our well-being, and the well-being of others, depends on how we navigate it.

Beyond ‘Active’ versus ‘Passive’ Usage

In an attempt to integrate research showing that different ways of using social media differentially impact well-being, several groups have distinguished between two general categories of social media usage: ‘active’ and ‘passive’ social media usage. According to this framework, the passive consumption of information on social media undermines well-being by increasing upward social comparisons. Conversely, the active use of social media to exchange information and to connect with others enhances well-being by enhancing social capital and support.

This framework has proved useful in pushing the field to think more mechanistically and has revealed differential negative effects of passive (vs active) use (Box 2). Nevertheless, further refinement of this framework is necessary; current research suggests that it is too coarse. As we discuss in the main text, although passively viewing other people’s social media profiles reliably undermines well-being, passively viewing one’s own profile has the opposite effect. Likewise, although actively using social media to garner support improves well-being, actively using it to cyberbully or spread moral outrage undermines well-being for others. Thus, a key challenge is to move beyond this nominal distinction to examine subtypes of active and passive social media use. In particular, two questions are pressing.

First, we need to understand how different motivations for using social media interact to influence well-being. Extant research has primarily focused on how different social media motivations operate in isolation. However, human behavior is multiply determined; multiple goals drive people’s behavior, which are activated to various degrees depending on individual differences and the circumstances people find themselves in [113,114]. And in some cases, motivations conflict. For example, a person may be driven to abstain from viewing others’ profiles to avoid feeling envy, but simultaneously motivated to share their emotions with others. Which of these motivations is stronger may influence whether and how people interact with social media and the implications that doing so has for their well-being.

Second, research is needed to examine whether people are aware of the implications that their social media behavior has for themselves and others. Our review suggests that an asymmetry characterizes how several social media behaviors impact the self versus others. For example, curating one’s profile improves how one feels, but promotes envy among others; cyberbullying disproportionately impacts the targets (vs perpetrators) of such behavior. Whether people are aware of these asymmetries is unknown, as are the consequences of informing them about them for regulating their social media behavior.

If social media have both positive and negative implications for well-being, one question concerns why the dominant narrative in the media has disproportionately focused on its dire consequences [6]. The newsworthiness of such headlines is likely to play some role in explaining this phenomenon, but we suspect it is not the only factor. In this vein, it is worth highlighting the fact that one of psychology’s most foundational findings concerns our tendency to overweight negative (vs positive) information [72,73]. Thus, it is possible that people form generalizations about social media’s overall well-being impact based on the negative effects they have in some situations (e.g., upward social comparisons, cyberbullying). A key challenge moving forward is to identify how to disseminate information about social media’s positive and negative implications without having the latter obscure the former.

From a basic science perspective, future research is needed to move beyond asking broad questions about the overall effects of social media on well-being (see Outstanding Questions). Rather, the strategy now should be to study the different psychological processes that explain how and why social media impact well-being differently, whether different social media behaviors have downstream effects that extend beyond well-being (e.g., to impact family and school life), and why these effects may vary for different people in different cultures guided by distinct social norms. Although we focused on two candidate processes in this review that have been the focus of extensive research, many other processes are waiting to be examined. Work should continue to profile how target processes operate in isolation but also explore how they interact (Box 3).

Studies that seek to address the latter issue should also consider the unique information-processing dynamics that may underlie different types of social media behaviors. Managing one’s online persona would seem, for example, to be a reflective act that requires time and deliberation to implement. Sharing emotions with others, by contrast, may be a more reflexively driven behavior. Understanding the degree to which different social media behaviors are reflexively versus reflectively driven has the potential to both illuminate the processes that underlie them and inform the development of interventions designed to enhance social media’s impact on well-being [102].

Focusing more on psychological processes also has the potential to provide insight into the question of how different social media platforms uniquely impact well-being. By focusing on the processes that different platforms activate, as opposed to simply comparing Platform A (e.g., Facebook) versus Platform B (e.g., Instagram), we can move beyond the nominal distinctions that distinguish platforms, to the more meaningful psychological variables that influence users’ experience (Figure 1).

This issue is also relevant to the emerging experimental literature examining the impact of manipulating aggregate social media use on well-being. Extant research manipulates social media usage in a variety of ways. Some work contrasts experimentally induced abstention against regular usage (e.g., [33]) while others contrast induced usage against an active or non-active control (e.g., [32]), and there is further heterogeneity within these broad approaches (e.g., in the length of abstention/usage, simple abstention vs deactivation of accounts). Each of these different manipulations may activate a different set of underlying processes that have implications for people’s well-being.

Studying psychological processes requires, however, that we utilize strong methods. The field’s overreliance on cross-sectional designs is a major weakness [35,36], yet cross-sectional research continues to proliferate. We urge researchers interested in exploring the social media–well-being relationship to incorporate experimental and longitudinal designs into their work to strengthen their ability to draw inferences about causality.

More work is also needed to validate the methodologies we use to study the impact of social media on well-being. We have already discussed the validity concerns associated with commonly used self-report Facebook usage variables. However, similar issues apply to other measures used in this area. For example, one prominent study counted the number of emotion words contained in people’s Facebook posts to draw inferences about how they felt although no validation data supported the use of such methods to track people’s emotions on social media [103]. As later research pointed out, counting emotion words does not track how people feel on Facebook [104]. The take-home point is simple: psychometrically sound measures are not a luxury: they are instrumental for valid inferences.

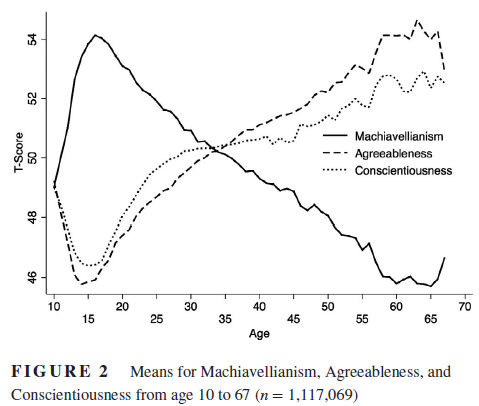

From a translational standpoint, there is a need to identify science-based interventions that enhance the positive and minimize the negative consequences of social media. There are at least three paths to studying these interventions (Figure 2). One involves directing people to use social media in particular ways, and then gauging the implications of such person-focused interventions. Much of the existing experimental work in this area takes this form. A second path involves examining how modifying the social media platforms that people use (with their informed consent) impacts the way they use them and how they affect well-being. For example, a platform could be augmented to promote the sharing of information that research suggests should enhance well-being. Finally, a third method involves a combination of the previous two approaches; that is, simultaneously educating people about how to navigate social media optimally and tweaking social media platforms to maximize their positive impact.

At least three pathways exist for process-focused social media intervention research. Person-centered interventions focus on changing how people use social media to enhance well-being. Potential ways of communicating this information include instructing individuals directly, relaying information through parents, teachers, or supervisors, and the creation of institutional policies. Platform-centered interventions involve changing the way that social media platforms function (with user consent) to enhance their likelihood of promoting well-being. Finally, the person + platform intervention pathway involves the examination of the effects of both kinds of intervention simultaneously.

Concluding Remarks

Social media, like the printing press, represent a kind of disruptive technology that appears once in a generation. Over the past 15 years science has done an admirable job advancing our understanding of the impact these media have on our well-being, but the work is by no means complete. Numerous questions remain. Given the energy and enthusiasm characterizing work in this area, and the enormous level of talent working on solving these questions, we suspect that the next 15 years will be ripe with discoveries that advance our understanding of how this ubiquitous technology influences our emotional lives.

Can we find a common lexicon to conceptualize the social media landscape? Addressing this issue is vital to solving social media’s jingle-jangle problem (Box 1).

Can we develop theory-driven frameworks to identify candidate processes that explain how social media impacts well-being and generate predictions about how they operate in isolation and interactively? Can such frameworks be used to distinguish between different social media platforms?

Can we make further distinctions within active and passive social media usage? Do different active and passive behaviors relate to different psychological processes? Are some behaviors more impulsive versus deliberate? How might these different behaviors impact well-being?

Do asymmetries in the way certain social media behaviors impact the self versus others help to explain why some harmful practices persist? If so, how can such information be utilized to inform interventions?

Can we systematize the way we perform experiments on social media? Some experiments direct people to abstain from using social media while others direct them to use it more compared with baseline. Heterogeneity also characterizes the time course of different manipulations, the measures used to document their effects, and the frequency of their administration. All of these factors could differentially impact study results depending on the nature of the process being manipulated.

How can we balance the need to perform studies quickly on an evolving technology without compromising the need to use valid measures and methods?

Can we design person- and platform-centered interventions that amplify the positive and diminish the negative implications of social media use on well-being?

How can we disseminate information about social media’s positive and negative impacts without having the latter obscure the former, given the documented tendency for people to overweight negative (vs positive) information?