Cultural evolution of emotional expression in 50 years of song lyrics. Charlotte O. Brand, Alberto Acerbi, Alex Mesoudi. Evolutionary Human Sciences , Volume 1 , 2019 , e11. Nov 7 2019. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2019.11

Abstract: Popular music offers a rich source of data that provides insights into long-term cultural evolutionary dynamics. One major trend in popular music, as well as other cultural products such as literary fiction, is an increase over time in negatively valenced emotional content, and a decrease in positively valenced emotional content. Here we use two large datasets containing lyrics from n = 4913 and n = 159,015 pop songs respectively and spanning 1965–2015, to test whether cultural transmission biases derived from the cultural evolution literature can explain this trend towards emotional negativity. We find some evidence of content bias (negative lyrics do better in the charts), prestige bias (best-selling artists are copied) and success bias (best-selling songs are copied) in the proliferation of negative lyrics. However, the effects of prestige and success bias largely disappear when unbiased transmission is included in the models, which assumes that the occurrence of negative lyrics is predicted by their past frequency. We conclude that the proliferation of negative song lyrics may be explained partly by content bias, and partly by undirected, unbiased cultural transmission.

Discussion

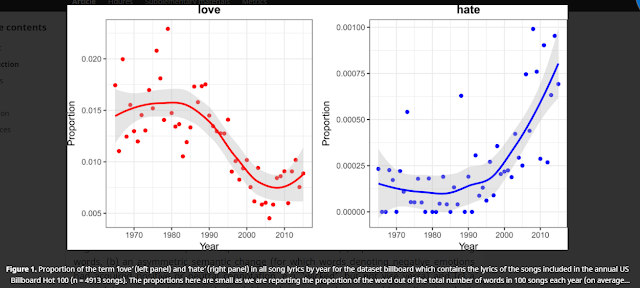

We analysed the emotional content of song lyrics in over 160,000 songs spanning the years 1965–2015. We found that the frequency of negative words increased over time, whilst the frequency of positive words decreased over time, and asked whether these patterns could be attributed to cultural transmission biases such as success bias, prestige bias, content bias or unbiased transmission. In the billboard dataset, containing top-100 songs from 1965 to 2015, we found an effect of unbiased transmission on positive lyrics, and an effect of content bias on negative lyrics. For the larger mxm databases we only found weak effects of unbiased transmission for both negative and positive lyrics.

The effects we found in all models are extremely small. This is partly because we analysed the data on the scale of each word, negating any need for averaging over lyrics and songs. Thus, the relative increase or decrease in the log odds is understandably small. Furthermore, our implementation of transmission biases is necessarily indirect and simplified given that we lack direct observations of song lyrics being copied. It is therefore unsurprising that the effects vastly reduced or disappeared when controlling for unbiased transmission, given how many other factors must be at play in the generation of song lyrics, both directional biases such as those we explored here and random processes (Bentley et al. 2007). For example, prestige can be realised in myriad ways (Jiménez and Mesoudi 2019), particularly in the music industry. The effect of various recording companies, the extent of media attention outside of the charts and the amount of money spent on music promotion may all play a significant role in an artist's apparent prestige, and is not necessarily restricted to the content of their music. Our implementation of ‘prestige’ as predominance in the charts therefore only captures one specific aspect of musical prestige.

The effect of unbiased transmission is, however, the largest and most consistent in all of our models. This result suggests there may be an effect of random drift, or random copying, in the emotional content of song lyrics over time. This is consistent with previous work showing that random copying can explain changes in the popularity of dog breeds, baby names and popular music (Bentley et al. 2007; Hahn and Bentley 2003), as well as archaeological pottery and technological patents (Bentley et al. 2004). Thus, rather than song-writers being influenced by the most prestigious or successful artists, they may simply be influenced by the emotional content of any of the available song lyrics in the previous timestep, which may happen to increase in negativity or decrease in positivity owing to small fluctuations. As in previous work, our results do not provide evidence of literal random copying by individuals as we do not have direct access to individual's copying decisions. Instead, random drift is posed as a baseline against which to compare evidence of other copying biases. It is possible that the population-wide patterns are not a result of unanimous random copying, but owing to a multitude of idiosyncratic causes that collectively cancel each other out to create the appearance of random copying (Hoppitt and Laland 2013). In this sense, any small fluctuation in negative words owing to a particular historical event, or owing to the emergence of a more negatively biased genre, may have caused an initial increase in negative lyrics, which became exacerbated by random drift.

The presence of a content bias in the likelihood of negative lyrics occurring in the billboard songs is noteworthy. This result suggests that songs with more negative lyrics are more successful in general, perhaps reflecting either a general negativity bias (Bebbington et al. 2017; Fessler et al. 2014) or an art-specific, or music-specific, negativity bias. Similar trends favouring negative emotions vs positive ones in other artistic domains support our finding. As mentioned above, Dodds and Danforth (2010) documented a decrease in frequency of positively valenced words, and an increase in negatively valenced ones in pop song lyrics (a similar result was found in DeWall et al. 2011). Morin and Acerbi (2017) found a similar pattern in centuries of literary fiction, with a general decrease in the frequency of words denoting emotions, explained by a decrease in words denoting positive emotions, whereas the frequency of negative words remained constant. It is worth noting that we were unable to look for content bias (with our implementation) in the mxm data as there was no ranking system. One possible way of determining the popularity or use of a song could be to look at how many times, or how often, its lyrics are searched for, and whether this correlates with negative content.

In general, the idea that negative emotions would be privileged in art is consistent with the hypothesis that artistic expressions may have an adaptive function, in particular as simulation of social interactions (Mar and Oatley 2008). According to this view, developed with literary fiction in mind but potentially generalisable to other expressive forms, art would provide hypothetical scenarios where we can test and train, with no risk, our cognitive and emotional reactions. From this perspective, simulating negative events is more useful than simulating positive ones (Clasen 2017; Gottschall 2012). Art expressing negative emotions, in addition, may hold more value for audiences seeking comfort from the knowledge that others also experience negative emotions. Indeed, studies have shown that people underestimate the prevalence of others’ negative emotions, and this underestimation exacerbates loneliness and decreases life satisfaction (Jordan et al. 2011). Furthermore, suppressing rather than reappraising negative emotions decreases self-esteem and increases sadness (Nezlek and Kuppens 2008)(Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008). This hypothesis is worth investigating in future research.

Our varying effects models suggested that most of the variation lay between artists. However, genre also showed considerable variation. We were unable to control for genre in the billboard data as genre information was not available with this dataset. This could provide a partial explanation for the differing results between the billboard and mxm datasets; indeed, Dodds and Danforth (2010) attributed the decrease in emotional valence within pop song lyrics to the emergence of more negative genres such as heavy metal and punk. Future work investigating the variation of emotional expression between different genres of music would be valuable. A further limitation of this study is that we restricted our analysis to comparing the content of each song with that of the songs from the previous three years of songs. Mechanistically this suggests that songs that are currently in the charts influence song-writers who are writing within three years of chart success, assuming that the time it takes to get from the song-writing process to chart success is three years or less. It is possible that these effects are stronger or weaker at different time points, such as within one or five years of chart success. Furthermore, although we controlled for artist, many songs in the billboard charts are in fact written by specially designated song-writers, such as Max Martin.

Overall this research contributes to the growing body of work attempting to quantitatively study trends in the domain of music (Youngblood 2019; Savage 2019; Mauch et al. 2015; Ravignani et al. 2017). Our starting result of an increase in negative emotions and decrease in positive ones in song lyrics is paired with similar findings regarding acoustic qualities. Using the same Billboard top-100 songs that we analysed, Schellenberg and von Scheve (2012) found an increase in minor mode and a decrease in the average tempo, which indicates that the songs become more sad-sounding through time. This seems to be part of a longer trend in Western classical music, where the use of the minor mode increased over a 150-year period from 1750 to 1900 (Horn and Huron 2015). The relationship between minor tone and negative valence of lyrics has been also studied, and confirmed, quantitatively (Kolchinsky et al. 2017). Analogously, studying more than 500,000 songs released in the UK between 1985 and 2015, Interiano et al. (2018) found a similar decrease in ‘happiness’ and ‘brightness’, coupled with a slight increase in ‘sadness’ (these high-level features result from algorithms analysing low-level acoustic features, such as the tempo, the tonality, etc.). They also found the puzzling result that, despite a general trend towards sadder songs, the successful hits are, on average, happier than the rest of the songs. In the same way, whereas we found that the higher the position in the billboard chart the more negative a song is, billboard songs are as a whole more positive than the songs in the mxm dataset, which contains more (and less successful) songs.

In this study we used cultural evolutionary theory to try to explain patterns in one of the most pervasive of human cultural practices, music production. More specifically, we tried to detect whether any particular transmission bias best explained the changing patterns of emotional expression over time. We conclude that, although we found weak evidence of success and prestige biases, these were overwhelmed by an effect for unbiased transmission. The presence of a content bias for negative lyrics remained, and this may be a contributing factor to the increasing in negative lyrics over time. A potential explanation for these results is that a multitude of transmission biases and other causes are at play. It is likely that small shifts, for example owing to historical events or the emergence of particular genres, may have nudged the production and transmission of negative and positive lyrics in opposite directions, and random copying exacerbated this trajectory. These possibilities should be explored more in future work. Overall, the exercise of precisely analysing large datasets to explain cultural change, if refined on relatively benign cultural trends such as pop music, could eventually be more expertly applied to areas of greater societal importance and impact, such as shifts in political beliefs or moral preferences.