The traditional occidental concept of the human mind seems to be essentially based on mind-body dualism deriving from the Cartesian distinction between the mind (res cogitans) and the body (res extensa). The mind-body dichotomy has been taken to imply not only that basic perceptual and motor functions are separated from higher order ones (Block, 1995), but also that the latter are exclusively based on the manipulation of abstract, amodal symbols and are largely independent from the former (Newell & Simon, 1972). In the last few decades, this radical view has been challenged by ever increasing psychological and neuroscientific evidence that human cognition is profoundly influenced by basic sensorimotor processes and that even complex concepts such as the abstract aspects of language are largely grounded on body representations and their relations with the world. This is the central tenet of a group of theories that are included under the umbrella definition of ‘Embodied Cognition Theories’ (ECTs). According to these theories, all human experience is grounded in the body, not only perceptual and emotional processes and social interactions, but also the acquisition and creative use of language (e.g., the use of metaphors), judgment capacities and the creation of cultural artefacts (Gallagher, 2005). Since their original formulation (Glenberg, 1997), ECTs have attracted the interest of many disciplines, such as psychology, psychotherapy (Khoury et al., 2017; Tschacher et al., 2017), education (Pouw et al., 2014), philosophy, anthropology, robotics (Hoffmann et al., 2010), artificial intelligence (Shapiro, 2011) and, last but not least, neuroscience (Freund et al., 2016; Kiefer & Pulvermüller, 2012; Mahon & Caramazza, 2008). However, ECTs do not refer to a unitary construct and each theory does in effect differ from another in the way it conceives the reciprocal relations between the body, the mind and the environment and the modalities by means of which bodily representations affect cognition. The various different theories range from a general idea of an instrumental role of the body in information processing (Körner et al., 2015) to a more radical view asserting that “all cognitive processes are based on sensory, motor and emotional processes, which are themselves grounded in body morphology and physiology” (Glenberg, 2015, p. 166).

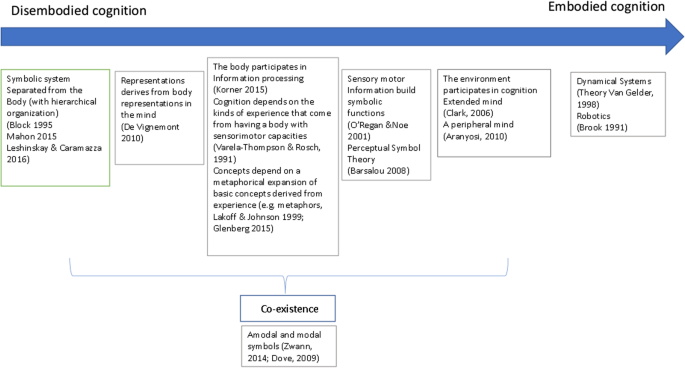

Importantly, however, a sort of continuum is identifiable within these various theories (Fig. 1). At one extreme of this continuum, there is a hypothesis that presupposes the hierarchical organisation of cognition with a symbolic system that is separated from the sensorimotor system that can merely activate motor responses (Leshinskaya & Caramazza, 2016). At the other extreme is the idea that cognition emerges from a dynamic circle of interactions between the brain, the body, and the environment without the need for symbols (Brooks, 1991; van Gelder, 1998). What distinguishes these two perspectives regards the role that the body and its connection to objects plays in cognition (Shapiro, 2019). The body may be considered to ‘participate’ in building cognition since cognition may be altered depending on the shape, size and experiences of the body (Glenberg, 1997; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Varela et al., 1991). From a different perspective, the body can be considered to be ‘constitutive’ in the sense that cognition would not exist without it (e.g., the Perceptual Symbol theory; Barsalou, 2008; O’Regan & Noë, 2001). Objects are only taken into account in some of these theories in which it is suggested that they participate in building cognition (e.g., the Extended mind theory, Clark, 2006; the Dynamical systems theory, van Gelder, 1998). An example is the act of writing and thinking at the same time, a task that gives a specific result due to the interaction between the brain and the body and thence to a pen and paper, and from there back again to the brain (Clark, 2006). Accordingly, if one changes either the gesture or the object, the final product will also be different. One might ask whether in this case the mind extends to the body (e.g., the Peripheral mind theory, Aranyosi, 2013) and also to the objects (Clark, 2006) or, alternatively, the mind incorporates the body and the objects it is interacting with (Borghi, 2005). This is a question that remains unanswered.

Recent studies on the link between embodiment and higher order functions in people with sensory deprivation highlight the importance of both sensory and conceptual representations (Ostarek & Bottini, 2021). For example, anterior temporal lobe activation in colour-knowledge tasks turned out to be very similar in congenital and early blind subjects (Wang et al., 2020). In contrast, activation in the ventral occipito-temporal colour perception regions was found only in sighted controls. This pattern of results points to the existence of two forms of object representation in the human brain: a sensory-derived and a cognitive-derived form of knowledge (Wang et al., 2020), with the former being experience-dependent and the latter experience-independent (Ostarek & Bottini, 2021). Crucially, the analyses of connectivity in Wang et al.’s study shows that the two systems relating to colour knowledge are integrated and part of a widespread network (Wang et al., 2020). Thus, a crucial question concerns not only whether but also how the two levels interact and if the sensory level is able to modulate and modify the conceptual level. If so, one can conclude that knowledge is embodied, although embodiment is not the only way the brain understands the world.

While no single clinical condition makes it possible to distinguish between the various different ECTs, alterations in the body may provide novel information on the different variables that play a role in these processes. Studies of amputees, for example, may highlight possible representational bodily changes that might, however, be due to multiple aspects, such as the visual appreciation of conspicuous changes in body shape as well as the somatosensory and motor disconnection between the body and the brain. In the following section, we focus on individuals suffering from spinal cord injury (SCI) in whom the general body shape is unchanged in spite of a massive somatosensory de-afferentation and motor de-efferentation. The specificity of this neurological model with respect to other clinical conditions will be analysed, then the changes in cognitive functions associated with SCIs are reviewed, starting from the representation of static and acting bodies, and continuing with an exploration of object and space representations. The potential contribution of these experimental data to the debate on embodied cognition will conclude the review.